Author:Açelya Dursun

Scent is one of the fastest and most immediate triggers in the human sensory system. As long as we breathe, smelling ceases to be a conscious choice and becomes a continuous, involuntary experience. For this reason, our relationship with scent is both intimate and unavoidable.

In recent years, contemporary artists have increasingly explored the potential of this powerful sensory medium, moving toward a field known as olfactory art. Scent is no longer confined to perfumery; it has become a carrier of artistic expression, political critique, identity, space, the body, time, and memory.

For centuries, art experiences in museums and galleries have been shaped by visual dominance. Touching is prohibited, tasting is impossible, and smell has often been ignored or relegated to the background. Yet many artists have begun to challenge this single-sense tradition by incorporating sound, tactile materials, and especially scent into their work.

Scent rarely appears alone within an artwork; rather, it merges with images, objects, space, or performance to create a multisensory encounter. This holistic approach draws the viewer into the work, blurring boundaries and transforming the experience from something merely “looked at” into something fully “inhabited.”

Conceptual Foundations of Olfactory Art

1. The Body, Bodily Politics, and Norms

One of the most powerful aspects of olfactory art is its direct relationship with the body.

Social taboos surrounding body odor, especially the pressure placed on women to be “odorless” are interrogated and subverted by many artists.

2. Space and Identity

People form political, economic, cultural, and emotional relationships with the places they inhabit. These relationships are often shaped by scent. Smell becomes an integral part of spatial memory and personal identity.

3. Time and Memory

Scent is the most potent trigger of autobiographical memory. A single smell can instantly recall a period, an event, or an entire life phase. Many artists build temporal narratives through scent, creating sensory pathways to the past or the future.

4. An Interdisciplinary Field

Olfactory art intersects with anthropology, neuroscience, engineering, biology, and perfumery.

This interdisciplinary complexity emerges from the layered nature of scent itself and opens new avenues for artistic and scientific research.

A Brief History: From Duchamp to Today

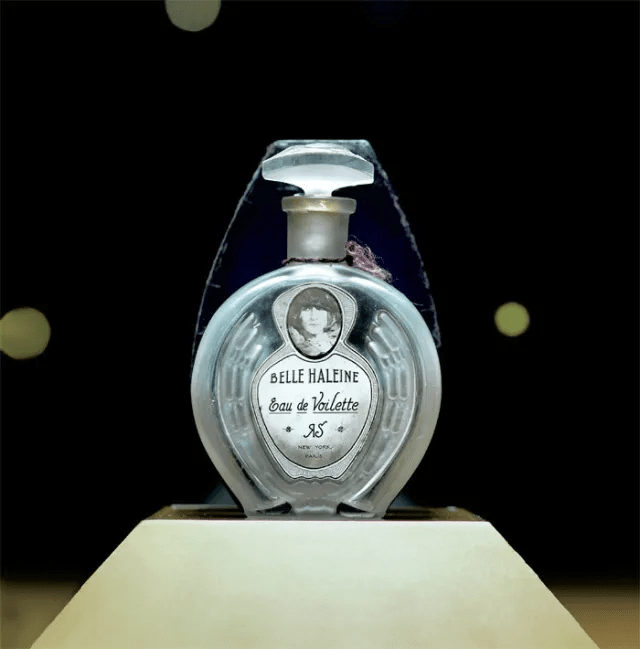

Marcel Duchamp, Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (Beautiful Breath, Veil Water), 1921, perfume bottle with label in oval box, 6 1/2 x 4 1/2 x approx. 1 1/2″.

Source: https://www.artforum.com/features/close-up-a-rrose-in-berlin-197115/

Although olfactory art may seem new, its roots reach back to the early 20th century.

- 1921 – Marcel Duchamp’s parody perfume Belle Haleine – Eau de Voilette.

- 1938 – The Scents of Brazil, a coffee-roasting performance presented at the Surrealist Exhibition in Paris, is considered the first olfactory performance in modern art history.

- 1960s – Fluxus and Arte Povera artists approached scent as an experimental material. Takako Saito’s Smell Chess and Spice Chess are notable examples.

- 1970s–1980s – Bill Viola’s installation Il Vapore, filled with eucalyptus steam, and Wolfgang Laib’s beeswax room-aromas.

These early explorations laid the groundwork for the contemporary olfactory practices that would flourish from the 2000s onward.

Leading Figures and Works in Contemporary Olfactory Art

Clara Ursitti – Eau Claire

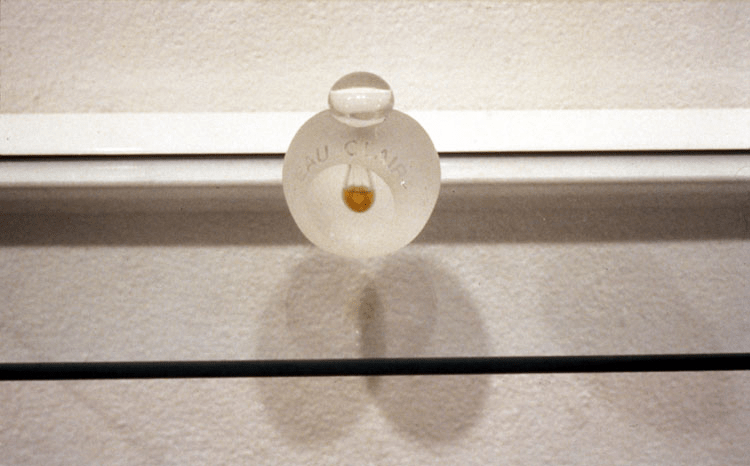

Eau Claire, Hand blown glass bottle with the artist’s scent

Source: www.claraursitti.com

Clara Ursitti has worked with scent for more than 25 years. What fascinates her most is the invisible, ephemeral, and environmental nature of smell.

Body odor, especially the demand for women to be “odorless” is central to her practice.

Eau Claire (1993) is an organic scent portrait created from the artist’s vaginal and menstrual secretions. Stabilized with alcohol and coconut oil, the work stands as a radical challenge to the visual portrait tradition.

According to art historian Caro Verbeek, every individual has a unique “odor print,” as distinctive as a fingerprint, making this work “one of the most personal forms of representation.”

Ursitti disrupts the notion of the female body as an object of shame, reframing it as a source of identity and agency.

Sissel Tolaas – FEAR of Smell / Smell of FEAR

Source: https://www.mediamatic.net/en/page/21095/the-smell-of-fear

Norwegian artist and researcher Sissel Tolaas is one of the most influential figures in the field, with a Smell Archive containing nearly 7,000 scents. She is also collaborating with the Max Planck Institute on NASALO, a scientific dictionary of smell.

Her project FEAR of Smell – The Smell of FEAR (2004) was created by capturing the sweat molecules of twenty men at the moment of fear. These molecular data were transformed into a sensory exhibition at MIT.

The work demonstrates how scent can record, translate, and communicate emotional states.

Peter De Cupere – SWEAT

Source: http://www.peterdecupere.net/

Belgian artist Peter De Cupere approaches scent as both an experimental material and a universal mode of communication.

His performance SWEAT (2010) began with five dancers consuming five different diets, since metabolism and nutrition strongly shape the smell of sweat. As the dancers performed, their perspiration soaked into their costumes. The collected sweat was then distilled and displayed in a glass container for visitors to smell.

The piece reveals the individuality of body odor and makes visible the invisible networks of scent that shape our everyday interactions.

Anicka Yi – You Can Call Me F

Home in 30 Days, Don’t Wash 2015, 78 × 122 × 50 inches

Source: https://www.anickayistudio.biz/

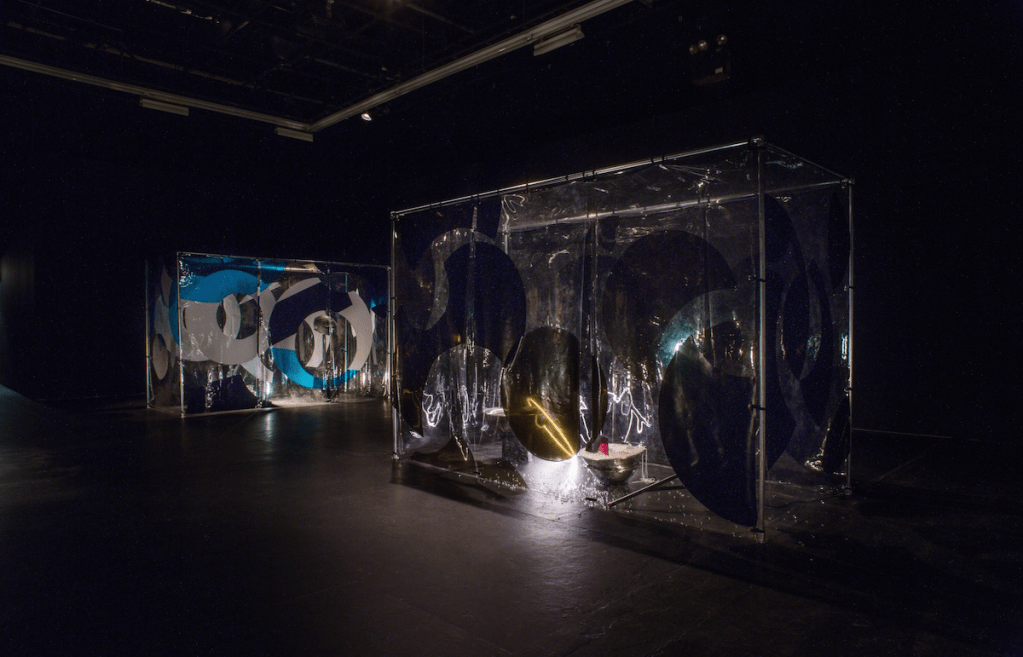

Anicka Yi describes scent as an “air sculpture.” Her installations combine bacteria, chemistry, fragrance, and spatial design to create multisensory ecosystems.

In You Can Call Me F (2015), bacterial samples from 100 women were cultured and transformed into a visible and olfactory exhibition. At the entrance, glowing vitrines displayed the bacterial forms, while five translucent tents inside the gallery released their corresponding scents.

Yi’s work opens up critical discussions around femininity, identity, hygiene culture, and the boundaries of disgust.

Maki Ueda – Smells for the Paris Agreement

Warmer Room & Cooler Room by Maki Ueda

Source: https://ueda.nl/smells-for-the-paris-agreement/

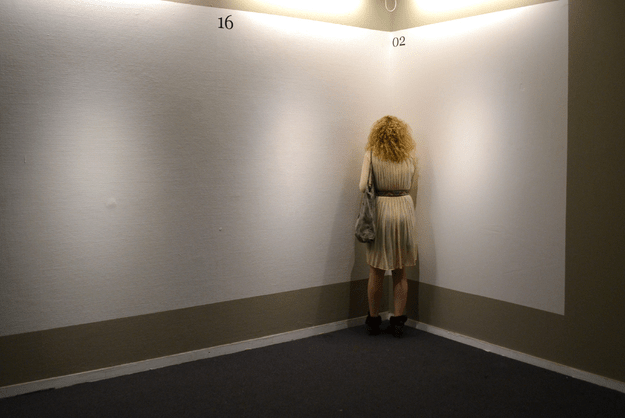

Maki Ueda aims to strip away visual distractions and present scent in its purest form.

Smells for the Paris Agreement asks a simple but profound question:

“Can a scent make a person feel warmer or cooler?”

Two airtight rooms were created, one scented to evoke warmth, the other to evoke coolness. The temperature in both rooms was identical, but visitors perceived them differently based solely on smell.

The work explores whether scent can be used as a sensory tool for environmental and climate awareness.

Scent is a language capable of making the invisible perceptible. As it moves beyond the limits of vision and sound, it opens intuitive and experiential pathways for artists. Olfactory art transforms the viewer from a passive observer into an active presence, someone who breathes, moves, and exists within the artwork.

For this reason, the layers of memory, emotion, and spatial perception embedded in scent continue to shape one of the most compelling creative fields in contemporary art.

Sources

“Sale 1209 / Lot 37 Marcel Duchamp,” Christie’s, September 2, 2012.

http://www.christies.com/lotFinder/lot_details.aspx?intobjectId=5157362

Caroline Cros, Marcel Duchamp. London: Reaktion, 2006, p. 100.

Bruce Altshuler, Salon to Biennial: Volume 1. Berlin: Phaidon, 2007.

Hannah Higgins, Fluxus Experience. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002.

Peter De Cupere, “Olfactory Art Manifest,” Olfactory Art Manifest. MIT, 2014.

Jim Drobnick, “Clara Ursitti: Scents of a Woman,” Tessera, June 2002.

https://doi.org/10.25071/1923-9408.25289

Susan Irvine, “Meet ‘Nasalnaut’ Sissel Tolaas,” Financial Times, May 11, 2018.

Alice Audouin, “Conversation with the Artist Sissel Tolaas,” Art of Change 21, June 2020.

Mine Değirmenci Aydın, “Peter De Cupere’nin Sanatında Bir İfade Biçimi Olarak Koku,” ODÜ Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi (ODÜSOBİAD), September 2021.

Finn Blythe, “Anicka Yi: The Artist Who Wants You to Smell Her Art,” Hero Magazine, April 7, 2021.

Karen Rosenberg, “Scent of 100 Women: Artist Anicka Yi on Her New Viral Feminism Campaign at The Kitchen,” Artspace.

Andrea Scott, “Scent of a Woman,” The New Yorker.

B. Cole, “Anicka Yi: ‘You Can Call Me F’ at The Kitchen,” Art Observed, April 4, 2015.

Maki Ueda, “MAKI UEDA,” n.d. https://www.ueda.nl/index.php?lang=en

Maki Ueda, “Smells for the Paris Agreement,” Smell, Taste, and Temperature Interfaces, 2021.

Yorum bırakın